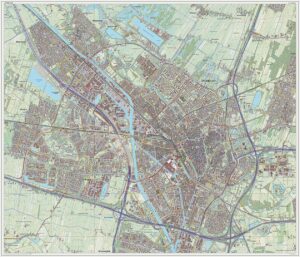

By Janwillemvanaalst – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=31746232

Understanding Utrecht

Well this is a pretty big town – about 370,000 or so as of last year (710,000 in their overall urban area, which includes “suburbs”) – they surpassed Bend’s 100,000 population way back in 1900. So they have grown fairly slowly over the years. It’s been around since the Roman’s built a protected fortification along the Rhine River way back. They’ve been through a lot. Back in the 1600’s they were conquered by Louis XIV of France (but they quickly came back out on top). They were also briefly occupied by the Germans in World War II. It is sobering to see large concrete bunkers aggregated around the nearby countryside, in a futile attempt to prevent being overrun.

Utrecht has similar transportation systems as we’ve seen in Copenhagen, but they are in the middle of a transition. We were able to talk to City Transportation Engineer and Planner, Ronald Thamse about the changes that are taking place – as it was interesting to experience their network while riding around.

Rebecca Lewis (U of O Professor) and Ronald Thamse (City of Utrecht, Transportation Engineer/Planner)

Ronald has worked for the City of Utrecht for about 20 years, but has lived in Utrecht practically all his life – at least 50 years in this City, so he has a wealth of understanding and history to share, both from growing up here and working on their transportation system.

Utrecht was an early adopter of protected bikeways. Because of this they have a well-connected network of safe and comfortable bikeways. They realized early on that residents would only begin to bike if they felt comfortable and safe – and they realized that begins at their doorstep. Protecting neighborhood livability and reducing cut-through traffic became one of their main means of creating safe and comfortable bicycling infrastructure that allows door to door service – you start bicycling near your house and are highly likely to be able to ride in a bikeway network all the way to your destination.

Photo of a residential street in Utrecht, Netherlands. The street width is not overly wide, yet accommodates on-street parking, sidewalks, and bike parking. Traffic calming has been added in a few ways. There are tiny, yet effective chicanes – sets of these small islands one on the right, followed by one on the left that allows bike riders to keep moving in a straight line, but car drivers have some horizontal deflection. Being two-way in a less-wide road also makes it a queuing street, so drivers also need to slow and let oncoming drivers on through.

Image shows a neighborhood school zone in Utrecht, NL. The area near the school has a raised intersection.

Image shows the end of the school zone and the transition back down to roadway grade from the raised area adjacent to the school

This is immediately adjacent to the school, still within the raised intersection area. There is a chicane built into the road, so it doesn’t go straight. The extra width in front of the school was landscaped.

The City of Utrecht developed supportive policies that helped them continue to grow while preventing clogged streets from traffic congestion and air pollution. As Ronald puts it, there are many things you can push or pull to influence mode share. “If you need fewer people in cars in order to reduce an overcapacity situation, or improve air quality, or meet sustainability goals, or have more land for development, or make a road easier to cross, whatever your goals, you can affect changes through: lane widths, number of lanes, turn lanes or not, modal filters, parking (quantities, prices, locations), cost of fuel, mixed use land use, etc. And provision of comfortable alternatives: transit headways, protected and complete bicycling network, etc. It really is up to your city what outcomes you want. The formulas are easy, it is up to you to implement them.”

One of these is decoupling car parking requirements from buildings. Ronald works downtown in the City of Utrecht’s staff office with 3,500 other urban planners and engineers. There are no car parking spaces provided, just 1,200 bike parking spaces. 30% of employees drive in – but they need to find a parking spot in a nearby parking garage (and have to pay for parking). The remaining employees take transit or walk in. Transit passes and bike parking are free to all the employees. So they are influencing mode split just by what parking they actually provide at the office (just bike parking) – but they can do this because it is safe and easy to bike, and transit is incredibly convenient. And because their employer pays for transit for them. That is a big perk.

The city of Utrecht has invested heavily in transit service with new buses, frequent headways (6 to 10 buses an hour on each route) and great coverage. They also are adding light rail serving bedroom communities that are within 15 km or so – a 9-minute train ride gets folks to the city center. And they make sure trains run every 15 minutes all day long. The obvious reliability and predictability are what allows many people to use the train or the bus. The trains are full – with standing room only during the AM and PM commutes. You can get a seat during other times of the day.

The region supports bike-train-bike trips by providing ample bike parking at the home station, and free bikes at the central station – part of your annual train pass. Employers provide free transit (so free transit and free bike) to their employees as a perk. Close enough to bike to work? They’ll give you a stipend to spend on a new bike every 4 years.

And Utrecht has been incredibly successful in achieving high bike mode share with their network – so successful (30% of all trips in the city are by bike, 30% are by car, and the remaining walking and transit) that they are now dismantling portions of it to achieve an even better level of service.

Yes, taking out a few of the protected bike lanes – this transition began in about 2012. Here is one example that explains the transition that has only recently begun taking place on key corridors in the downtown area:

Ronald noted that his worst project, the one he regrets the most, was building a 1-mile stretch of protected bike lane in 2005 – the part he regrets? The width was just 2 meters, 20 centimeters. For us foot/inches folks this is a is a 7’+2″ protected bike lane. And he regrets it. Because it was too narrow. There were so many people bicycling that it was delivering a poor level of service – too crowded during the peak hours. He was relieved when he got to correct the design last year – they converted the entire street over to bike riding. A shared street, that now carries 25,000 people a year on bicycles – in just two shared lanes. Add in another 5,000 people on the bus plus some cars, and the corridor now carries over 30,000 people. In a 60′ ROW.

And the side benefit to the abutting properties – there is now ample width for street cafes, and outdoor retail displays. The area is a thriving economic driver for the neighborhood. This is fascinating.

This is the intersection across Lucas Bridge where the conversion takes place. The protected bike lane runs to a signalized intersection. There is a bike signal coordinated with the intersection’s traffic signal. The bike stop bar is ahead of the car stop bar. The bikes get a green before the cars and move into the shared road ahead of the cars. The bike signal changes to red and then the cars get a green signal to enter into the shared street after the bikes. The bikes set the speed of the street as they have priority.

![]()

This is the beginning of the transition from Nobelstraat (Nobel Street) with its fully protected bike lanes on each side to a shared street. (just for fun note the bus stop has a small raised crossing to the platform, which also helps ensure bike riders yield to transit riders crossing to and from the bus).

This is the shared portion of the street along Nachtegaalstraat (Nightingale Street). Comfortable bike riding, even though there are cars and buses allowed on the street. The color helps (red indicates bike facility), but also the posted speed is 30 km/hour (18.6 mph), and the road is narrow (just 22′ wide), with a color-scheme so the lanes look narrower.

This is the street decal located on either end of Nachtegaalstraat (Nightingale Street) that is located at the beginning of the shared lane road portion of this street. – it means bikes have priority.

Check out the google map as you can zoom in to check out the details. The left side of the image has the protected bike lanes both sides (on Nobelstraat). The right side of the image is the shared street (red pavement color) on Nachtegaalstraat (Nightingale Street). The transition takes place over the Lucas Bridge where many cars make the left rather than go through at slower speed.

https://www.google.com/maps/@52.0929335,5.1270747,130m/data=!3m1!1e3

These crosswalk islands narrow the lanes slightly, but provide a place to cross Nachtegaalstraat (Nightingale Street).

The current Utrecht protected bike lane standard width is 3 meters wide (just under 10 feet wide) and 4 meters wide if two-way (just over 13′ wide).

What is the result of not only a complete network, but wider bike facilities?

In Utrecht we are more often going to see families riding in a group. Teenagers riding in a bunch. Young kids riding out all on their own. Little kids riding on little bikes near their parents. This is very different than Copenhagen. In Copenhagen most protected bike lanes were in that 6 to 7′ wide range – and they were crowded. So crowded that we didn’t see that much side-by-side riding. Too much pressure to get passed by another person. And this really reduced young riders, particularly during the peaks, as the sheer number of bike riders in such a narrow space would be way too intimidating.

Really common scene – we see more seats on bikes in Utrecht than in Copenhagen.

Side-by-side riding, the widths of the bicycling facility impact how social it is – when things can be social, more people will do it. And community is forged.

taken from a street side cafe seating area, these two people are able to ride side by side.

Can any community just skip the protected bike lane phase and move directly to the bikes get the whole street phase? It would save us a lot of trouble. Must we create our system in such a linear transformation?

I don’t think we can skip entirely, but it shows us that we can create quality biking facilities on our neighborhood greenways and our shared streets in Bend, Oregon – if we create proper transitions between protected bikeways and shared roads and we manage the speeds and traffic volumes to enable everyone to feel comfortable and safe bicycling on the street.

Lessons for Bend

One set of transitions the City of Bend can work on is where the bike lane ends on Wall Street heading south and entering the shared road space south of Greenwood Avenue – same northbound on Bond Street. Both of those are in awkward locations, and really leave any bike rider vulnerable and without a clear way to take the lane. This leaves out so many potential riders into our downtown (young, elderly, most adults, etc.).

In order to attract and support a wide range of ages, and abilities, wider separated facilities for people biking, are important. Transitions are important. Network connectivity and continuity is critical. Make sure you create route continuity, even if you have to have a merely adequate facility (until you can build the separation or the full width) – every piece of the puzzle is important.

4 Comments

Marc Schlossberg · July 10, 2022 at 5:30 pm

Very interesting to follow along with you!

Robin · July 10, 2022 at 9:13 pm

It is really amazing what Utrecht has done for transportation here. It is easy to drive, bus, walk, and bike. The details are pretty fascinating.

David Green · July 11, 2022 at 4:12 am

I love the example of induced demand…for bikes!

Our streets are so wide that we have lots of room for wider and protected bike lanes, if we’re willing to slow traffic with narrower lanes and raised crosswalks! These are such great examples.

David Green · July 11, 2022 at 4:15 am

I love the example of induced demand…for bicycles!

Many of our streets are plenty wide for wider and protected bike lanes, if we’re willing to slow traffic with narrower lanes and raised crosswalks. These are great examples and reminders of what we could do!